Microscopes

Science is abstract. From electrons to cells, these fundamental elements lie beyond our sight, yet they power our computers, cure diseases, and shape the modern world. Microscopes transform the abstract into reality, unlocking innovations that truly define humanity.

A microscope is a tool for enlarging the image of a smaller object. It allows the operator to view and analyze miniature structures at a tangible scale.

Microscope types

There are two main types of microscope: Optical microscope and Electron microscope.

Optical Microscope

Optical microscopes (compound microscopes) are found in nearly all labs, from schools to research centers. When you think of a microscope, the image that pops up is probably an optical microscope.

Optical microscopes enlarge miniature objects by helping your eyes converge light rays better. This is achieved by shining a light ray behind the miniature object, which travels through the object (usually a sample slide); two convex lenses can be used to magnify because they can focus the image at a closer range than the human eye.

A simple microscope, which consists of one lens, can also magnify an image, but it is less effective than optical microscopes.

They usually max out at 1000x magnification and are commonly used for analyzing bacteria and animal cells.

There are different kinds of optical microscopes assembled with different structures. Some require multiple mirrors and convex and concave lenses to redirect light rays.

However, their underlying principles are the same.

The word "microscope" refers to "optical microscope" in the following sections.

Electron Microscope

Electron microscopes take magnification to a whole new level. You can zoom into individual atoms using a transmission electron microscope.

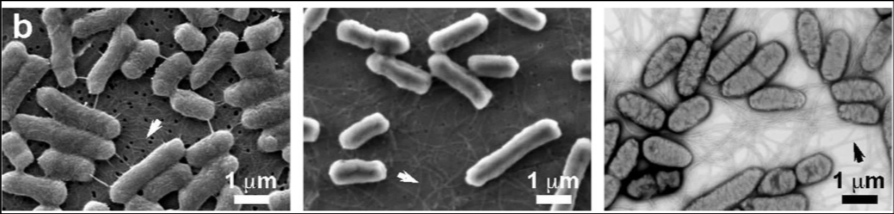

An electron microscope takes an image by shooting electron beams at the object and receiving the electrons using a sensor. There are two kinds of electron microscopes: Transmission Electron Microscopes shoot electron beams through a thin object, and Scanning Electron Microscopes use electron beams to scan through the object's surface.

Transmission Electron Microscopes (TEM) are more complex and can produce images with higher resolution. Their max zoom is roughly 50 million times (0.05 nm). Shooting through the object allows the image to reveal the internal structure of the sample (like an X-ray).

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) can scale up to 1 million times (1 nm). It scans the surface of the sample like a printer and receives the electron using a sensor. Although it is less powerful than the transmission electron microscope, it is still one thousand times more powerful than optical microscopes.

Electron microscopes are commonly used for analyzing viruses, engineering materials, and designing computer chips.

However, this level of technology comes at a cost. SEMs can cost between 70 thousand to 1 million USD, while TEMs can cost up to 10 million USD!

Aside from the cost, electron microscopes cannot produce a colored image because it is natural. The colored electron microscope images are fake colors processed by computers.

Microscope Structure

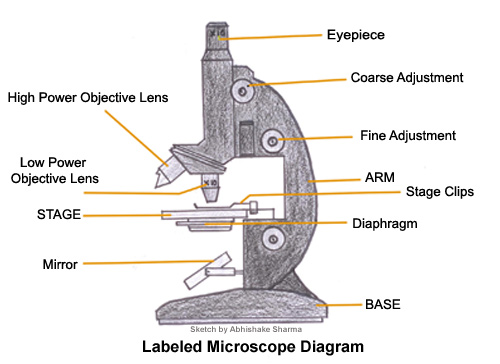

Below is a labeled microscope diagram (ASM Blog, n.d.):

The two lenses are the eyepiece and the objective lens. The stage and stage clips hold the sample. The coarse and fine adjustment knob adjusts the focus of the lens. The mirror and the diaphragm direct and control light to the sample. The arm supports the upper microscope structure. The base supports the whole microscope structure.

The eyepiece is usually 10x in magnification, and the objective lens can range from 4x to 100x. Hence, the total magnification is .

How Microscopes Work

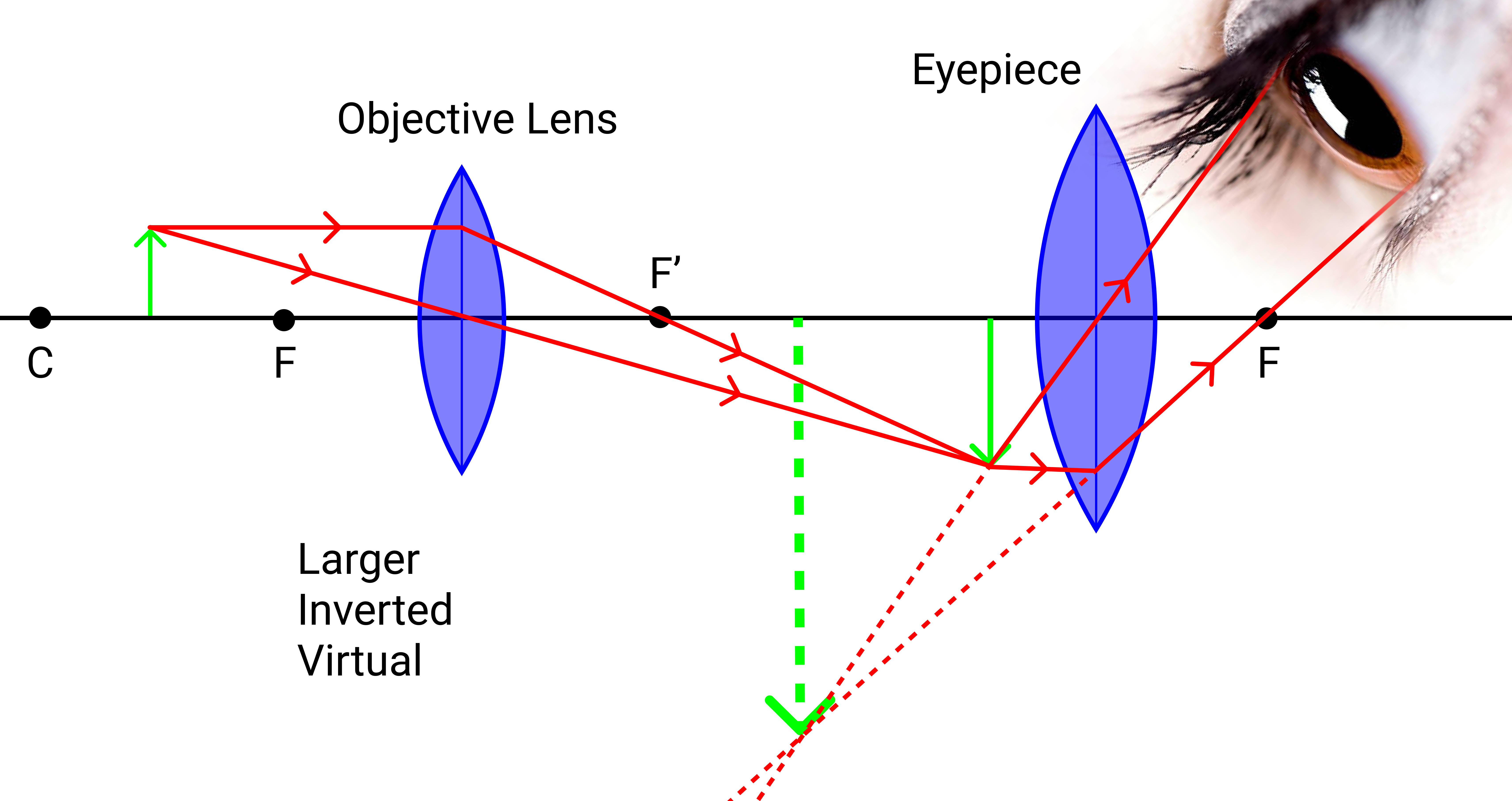

We drew a diagram to help understand how the microscope works:

The light source is produced behind the specimen. (We will ignore it here and focus on how the light rays travel).

First, the light ray travels past the specimen to the objective lens. The parallel ray will bend to the focal point while the ray intersecting the origin will not. The light rays continue to travel until the two light rays intersect to form the first real, inverted image, which is larger than the original image.

Next, the observer views behind the eyepiece. The light ray converges (following the parallel and origin intersect principle), forming a large, inverted virtual image.

The significantly larger virtual image can form anywhere behind the eyepiece.

The larger virtual image is inverted. Hence, when you move the stage to the right side, the observer will see the stage moving to the left side.