Binary Fission

Binary fission is when a bacterial cell reproduces asexually by elongating the cell body and separating the two new "identical" cells using a cell wall. More intro info

Like mitosis, the sub-processes that aid binary fission can happen in parallel.

Let us dive in on how binary fission works in a bacterium.

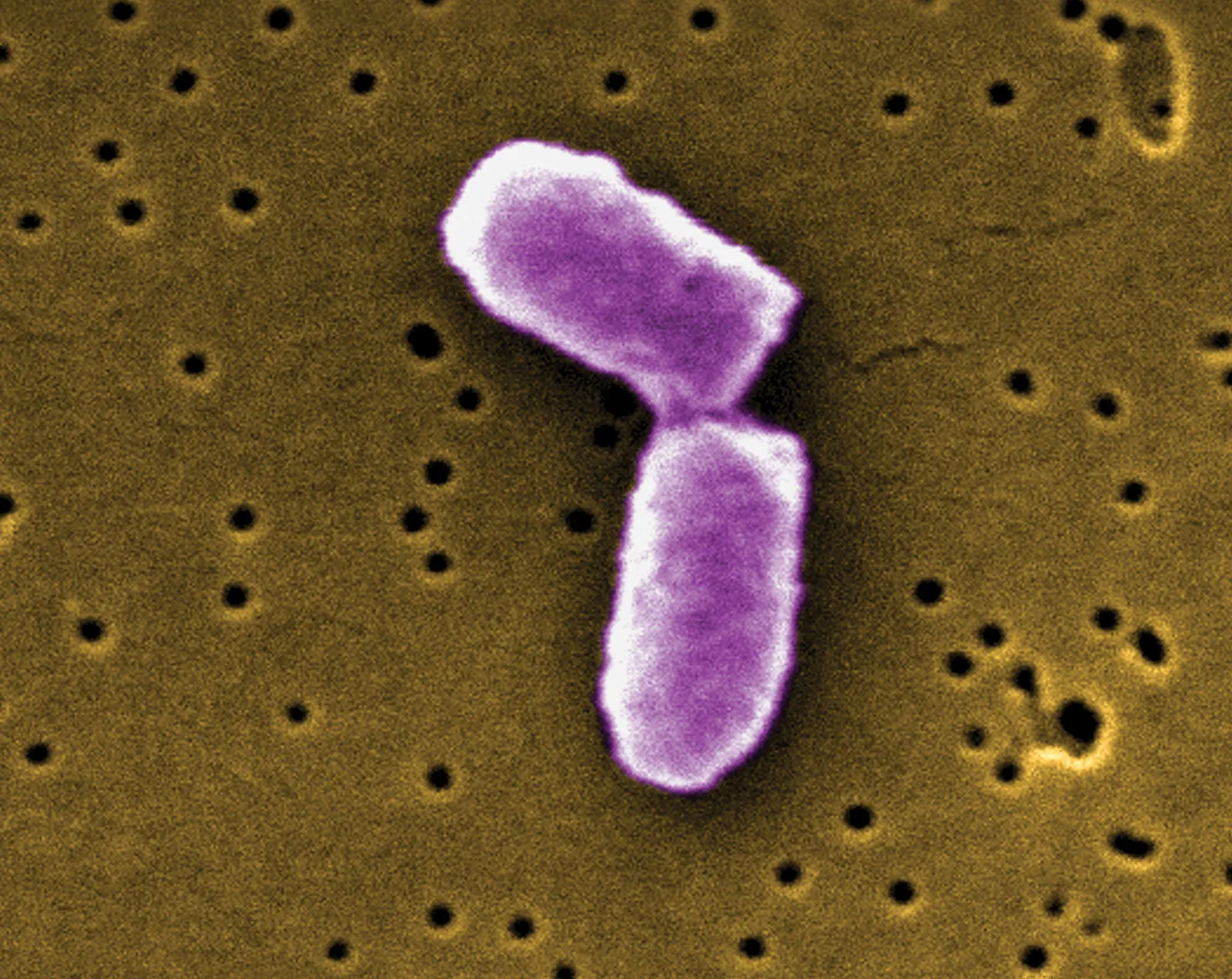

Image 1: A real bacteria undergoing binary fission (Britannica, 2024)

DNA Replication

Two identical are replicated because we will produce another identical bacterial cell. After the cell grows for a while, it needs to activate the replication procedure using , a common protein for initiating replication. The chromosome is a connected at the origin of replication to form a circle.

A group of proteins called travels to the origin of replication and replicates bidirectionally. The will extend to the left and right sides of the origin in the circle. proteins include , which unpacks genetic information, (synthesizes short ), and , which creates molecules using (the foundation substance for and ).

Under ideal growing conditions (provided in a lab), a bacteria takes an average of 40 minutes to divide. However, some bacteria, like E. coli, only need 20 minutes, as there are two (or more) origins of replication for cloning. This makes the replication process happen two times faster.

More complex substances are involved, but these essential substances allow replication.

Pre-Cytokinesis

After the is replicated into two bundles of chromosomes, the cell needs to be split exactly in half to retain the "identical" mindset. Hence, a Z-ring and other proteins are formed to aid this process.

Before we start, "Fts-" stands for Filaments Temperature-Sensitive protein. They are a group of divisome proteins that are vital for the division part of binary fission.

FtsZ protein, or the Filaments Temperature-Sensitive Z protein, is one of the most significant proteins in the binary fission process as it forms the Z-ring. FtsZ protein is related to the tubulin protein group, which are cytoskeleton proteins.

A Z-ring will be slowly constructed using a chain of FtsZ protein in the cytoplasm (configured in a loop) before the actual cytokinesis. However, a floating Z-ring would be useless. This is where the FtsA and ZipA protein comes in and anchor the ring to the cell membrane. Both proteins form actin-like filaments, which are structured like steel cables. Since we want two identical cells, the anchors must be placed in the middle of the cell. To find the center of the bacteria, the Min group protein moves back and forth to search for the cell's midpoint.

After the FtsA and ZipA protein anchor is placed in the correct spot, the Z ring contracts and pulls down the cell membrane to form a division septum. However, the cell wall is not completely pulled down to retain the bacteria's shape. We will discuss how the cell wall is cut and reconstructed later.

Before cytokinesis occurs, we must ensure the bundle is split correctly via the Ftsk protein. The FtsK protein binds to the replisomes and coordinates chromosomes to segregate. The actual segregation will be done using translocase proteins (a group of proteins that assists the movement of other substances).

Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis is the process where the "identical" daughter cells are segregated and completely detached from each other.

They may not be "identical" because plasmids may not spread evenly between the two cells.

First, the cell membrane and the cell wall contract using the Z-ring. The two bundles will split apart using the FtsK protein and translocase proteins. Then, the cytoplasm divides and forms a septum. The Z-ring continues to pull down the cell membrane and the cell wall until the whole cell separates at the septum.

Done! A fresh bacteria is reproduced! But how does the cell wall grow and segregate?

Cell Wall Formation

There is a peptidoglycan layer in the cell wall of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. In this explanation, we will use gram-positive bacteria because the Novato bacteria are gram-positive.

The cell wall is formed by peptidoglycan synthesis.

What are they made of?

The peptidoglycan layer forms by peptidoglycan synthesis. Each peptidoglycan molecule is a polysaccharide assembled using two glucose substances () and acid () cross-linked together with a bond (a carbohydrate bond) in an alternating pattern. A peptidoglycan layer is assembled by chaining peptidoglycan molecules in a uniform pattern.

bond is read as "beta one four glycosidic bond".

Meaning:

- is a type of orientation of the bond.

- means carbon is connected to carbon .

- is a carbonhydrate bond.

The cell membrane (both inner and outer membrane) is a phospholipid bilayer, two layers of phospholipids arranged in a sheet, with the hydrophilic head facing outwards.

The tail is hydrophobic while the head is hydrophilic!

However, the peptidoglycan will not stick to the cell membranes, so the periplasm is used as a "glue" and "spacer" between the peptidoglycan layer and the cell membrane (it works just like a cytoplasm).

Cell Wall Formation Process

The first stage of peptidoglycan synthesis is the synthesis of and using glucose. and are synthesized in the cytoplasm through a series of biochemical pathways. (New sugar molecules)

P.S. You can stop the synthesis to kill the bacteria.

New and molecules are now hanging around in the cytoplasm. Let's convert the sugar molecules into a basic building block of the layer. To assemble this block, we need to bind with , and bind with a chain. Now, this basic structure is ready for construction!

The chain is composed of three to five amino acids chained together with the bond (seems like the entire layer is chained using this bond). The amino acids include , , , , and .

To transport the building block from the cytoplasm to the peptidoglycan layer, we need to bring it up to the cell wall through the cell membrane. This is where bactoprenol comes in. Bactoprenol acts as the carrier chemical for the structure.

Now, the bactoprenol binds to the and starts dragging the structure past the cell membrane to the peptidoglycan layer. Let us start attaching the structure! But there is no place in the layer, so we need to cut the glycosidic links using autolysin.

The autolysin cut is "a bit dangerous" as there is a hole in the cell wall (the cell membrane is still holding it though). The osmosis effect will try to burst the bacteria.

P.S. This is a way to kill the bacteria.

The layer is now ready for insertion! The structure will be moved in place (around the peptidoglycan layer), and a new bond will be formed by the glycosylase enzyme.

Ta-da! The peptidoglycan layer just grew! The bactoprenol is reusable, so it travels back to the cytoplasm for the following building cycle.

P.S. You can inhibit bactoprenol movement to kill the bacteria.

Final Stage

Once the septum and the cell wall are formed, the bacteria is ready for segregation.

The two daughter cells are pulled apart, aided by proteins.

And that's it! Two new daughter cells are born. That's roughly how binary fission works. Many antibiotics target the binary fission process; we will discuss that later.